Recap from A firsthand account – PART ONE

Towering at 6,961 meters (22,838 feet), Aconcagua reigns as the highest peak in the Americas—and indeed, the tallest mountain outside of Asia. For mountaineers across the globe, it stands as a coveted challenge. Though its Normal Route is non-technical, the climb is far from easy.

It demands not just physical endurance and careful acclimatization. It also requires an unshakable mental resolve. Among the most effective acclimatization strategies on this route is the ascent of Bonete Peak (5,005 meters). This nearby summit offers a valuable preview of high-altitude conditions before the final summit push.

In December 2024, Sauraj and I set out on one of our most ambitious expeditions yet—to scale the roof of South America. The very idea of venturing into the heart of the Central Andes filled us with anticipation. But what made this journey even more special was the chance to explore an entirely new continent. Neither of us had stepped foot on it before.

A Birthday Celebration on Aconcagua ‘s Bonete Peak

On the morning of December 11th, I woke to a steel-grey dawn, the sun still hidden behind the massive silhouette of Aconcagua. The cold bit through our layers as we geared up in full trekking kit. But beneath the frost and fleece, I couldn’t stop grinning. After all, how often does one celebrate a birthday climbing a peak in Argentina’s Central Andes? And that too within sight of the highest mountain in South America—Aconcagua, a crown jewel of the Andes Mountains, the world’s longest mountain range?

Our small team—Masaki, Sauraj, and I—set off from Plaza de Mulas Base Camp (4,370 m) just after breakfast, led by our local guide, Rubén. Our objective: Pico Bonete Peak, a prominent acclimatization summit due south of the camp.

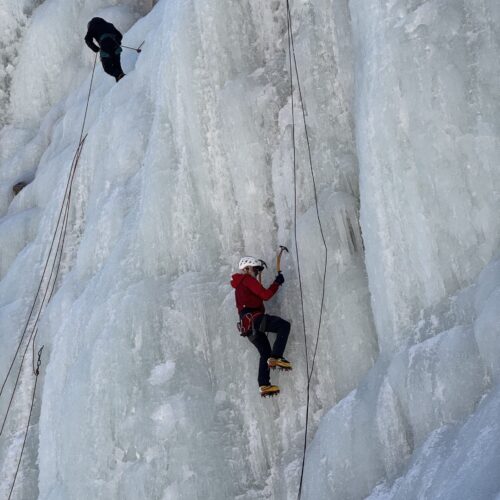

Today’s Route

The route began with a unique challenge: crossing a small glacier, where we had our first encounter with the surreal beauty of Nieves Penitentes. These are tall, blade-like ice formations sculpted by the relentless sun and dry Andean wind. These jagged pinnacles, rising like frozen daggers, are a distinctive feature of Aconcagua’s glaciers. They serve as both a visual spectacle and a vital source of meltwater for climbers. We would cross similar icy terrain multiple times en route to Bonete.

As the sun finally crested over the eastern ridge of Aconcagua, the chill quickly receded.

Warm light spilled onto a large, dilapidated structure just a few hundred meters from Plaza de Mulas.

Standing in stark contrast to the surrounding wilderness, this was the Aconcagua Hut—a once-operational mountain hotel. Though now shuttered, it had once offered meals, lodging, and respite at base camp altitude. We paused to admire its weather-worn stability. We couldn’t help but feel a pang of regret at the wasted potential of such infrastructure in this remote and awe-inspiring environment.

Leaving the hut behind, we pressed on. The terrain became rougher, a vast expanse of fractured stone and scree, devoid of any vegetation. We crossed two more glacial sections, carefully navigating through the needle-like penitentes. Each crossing demanded patience and balance. Sharp ice, shifting footholds, and the ever-present thin air reminded us we were very much in the high mountains.

Bonete’s Summit Ridge

The final push to Bonete’s summit ridge involved a steep scree slope, stitched with switchbacks.

Footing was loose, each step threatening to slide back twice the distance gained. While climbing up was an effort, the prospect of descending this slope seemed even more precarious. It almost guaranteed a few falls or at least a sprained ankle if we weren’t cautious. Under the fierce Andean sun, with jagged brown peaks surrounding us, the landscape felt otherworldly. It was easy to imagine this as a scene from Mars—barren, beautiful, and brutally demanding.

As we approached the summit block of Bonete Peak, Rubén led us away from the direct face and onto a narrow, exposed traverse around the right side. The trail was razor-thin and dramatic, offering sweeping views but no margin for error. Finally, we scrambled up the west shoulder ridge on all fours and reached the summit just before noon. At the top—marked by a metal cross wedged between a pile of rocks—I paused. With Masaki, Sauraj, and Rubén beside me, I took a moment to reflect on the sheer joy and privilege of celebrating another year in this way. Not with cake and candles, but with crampons and commitment.

In that stillness, I felt deeply grateful for the life I’ve chosen—a life defined by adventure, friendship, and high-altitude dreams. Thankfully, the wind was unusually calm. We found a few precariously balanced rock slabs just below the summit and sat down to rehydrate and enjoy a packed lunch. It was made up of two very tasty Ham Cheese Sandwiches. From this unique vantage point, Rubén began pointing out the legendary Aconcagua Normal Route.

Features of the Route unfolding like a mountaineer’s map:

- Plaza de Mulas Base Camp sat below us, and just above, we could trace the trail crossing a narrow glacier leading to Camp 1 – Camp Canadá (~5,050 m), a gently sloping camp perched on a rocky ridge. Often used for acclimatization carries, some teams bypass it and head straight for Camp 2.

- The route then veered left and upward, climbing the shoulder of the mountain before cresting a ridge—beyond which sat Camp 2 – Nido de Cóndores (~5,570 m). This expansive plateau is often the main staging point for summit attempts and offers better protection and space for tents.

- Though we couldn’t see Camp 3 (Colera Camp – 5,950 m) from our angle, Rubén pointed out a series of jagged rock spurs just behind which climbers pitch tents to escape the brutal high-altitude winds. Aptly named, “Colera” reflects the physical torment many endure here on the eve of summit day.

- Beyond that, we could clearly identify Portezuelo del Viento (~6,400 m)—a wind-exposed saddle that’s notorious for turning climbers back due to relentless gusts.

- Further still lay The Traverse (6,400–6,600 m), a long, diagonal path across Aconcagua’s upper north face, followed by the final crux: La Canaleta (6,650–6,850 m). This steep gully of loose scree and rock is infamous for draining whatever strength remains before climbers reach the summit ridge.

Even from the summit of Bonete, Aconcagua towered above us, majestic and intimidating in equal measure. From this vantage point, it wasn’t just the altitude that took our breath away.

It was the enormity of the mountain, the challenge it presents, and the respect it commands.

Later that evening, back at Base Camp, I was pleasantly surprised by the Camp Staff before our dinner with actual cake and candles. And of course, birthday songs and greetings. It was an excellent birthday, where I got to climb, have cake and eat it too.

The First Rotation – Camp 1 – Camp Canadá (~5,050 m)

The next morning, we took things slow. A late breakfast at Plaza de Mulas Base Camp allowed the morning sun to warm the mountain face before we set off. We crossed the narrow glacial strip that separates base camp from the massive northwest face of Aconcagua. Unlike the fast-paced summit push that would come later, today was part of our acclimatization plan. We were doing a load ferry to Camp 1 (Camp Canadá) at 5,050 meters.

The previous evening was spent meticulously reorganizing our gear. We packed additional equipment to leave higher on the mountain, reducing our burden for future rotations. This “carry high, sleep low” strategy—known among climbers as a load ferry—is essential for successful high-altitude acclimatization.

Standing outside the dining tent with a cup of coffee in hand, I gazed up at the looming face of Aconcagua. Dotted along its slopes, we could already see the silhouettes of climbers zigzagging their way up toward Camp 1. Soon, we would follow their trail. We had intentionally delayed our start.

The northwest face remains in shadow until mid-morning. During those hours, the mountain is bitterly cold and often windy. It wasn’t until the sun crested the ridgeline—around 10:00 AM—that the chill finally began to ease. With rucksacks packed heavy with climbing equipment and personal gear, we stepped onto the trail. Ruben led the way, followed by Sauraj, Masaki, and me taking up the rear. The air was thin, and our pace slow and measured.

This stretch is often described as the first real test on the Normal Route of Aconcagua. Leaving behind the relative comfort of Plaza de Mulas, we ascended steadily on a well-worn zigzag path. The trail cuts through volcanic scree, gravel, and loose stone. It demands constant attention to footwork—especially with the added weight of our packs.

Continuing the climb

As we climbed higher, the switchbacks grew steeper, and the landscape more barren. There was no vegetation—only stark, burnt-orange rock and sky. The Andes Mountains can be brutal in their simplicity, but also profoundly beautiful. Far below, the Horcones Valley shimmered in the morning sun.

Above, Aconcagua’s summit remained out of sight but ever-present.

Around the halfway mark, after two hours of steady climbing, we stopped to catch our breath.

The break spot resembled four massive stone spires jutting out of the mountain—almost like a giant’s hand emerging from the earth. We laughed at the surreal formation, took a few photos, and layered down as the sun rose higher.

Continuing upward, the final stretch of the trail veered toward a towering rock outcrop.

Scrambling up a short but steep section, we arrived at Camp Canadá. Spread across a gently sloped ridge, our dome-shaped tents stood out in the otherwise lifeless landscape. Unlike the compact two-person tents used at lower camps, Camp 1 featured large expedition-grade dome tents. They were designed to withstand Aconcagua’s harsh weather for weeks at a time. These shelters were made from heavy-duty synthetic canvas stretched over metal frames, bolted together for strength.

The toilet set up

A large, oblong dome caught my eye. Built on a solid frame like the others, it was split into two sections by a canvas screen. Curious, I ducked inside, expecting a semi-permanent toilet. Instead, I found a pink biohazard waste bag anchored with a rock—and nothing else.

Perplexed, I called out to Ruben. Grinning, he walked in holding a black garbage bag. “This is how we do it here,” he said. We had to squat over the black bag, double-bag the waste, and drop it into the pink one—part of Aconcagua’s Leave No Trace system.

It was environmentally sound but came with an awkward downside: zero soundproofing. If two climbers went in at once, let’s just say, it made for some unforgettable moments.

Heading back down

By 3:30 PM, we secured our gear, left the loads stashed in camp, and began the descent back to Plaza de Mulas with light packs. What had taken us 4.5 hours to climb, we now descended in just 2 hours, skipping nimbly down the trail that had challenged us earlier. Walking back into base camp felt surreal.

Just a few hours away, Camp 1 had reminded us of the stark, wind-blasted reality of high-altitude living.

Plaza de Mulas, with its comfortable tents, hot meals, and camaraderie, felt like a small paradise in comparison.

Two days of sustained climbing, elevation gain, and load-carrying treks had left us physically tired—but deeply satisfied. Our bodies were beginning to adapt. That night, I slept better than I had on any previous night on Aconcagua.

To know what happened next.. read Part Three here!

Follow us on Social Media – LinkedIn | TripAdvisor | Instagram